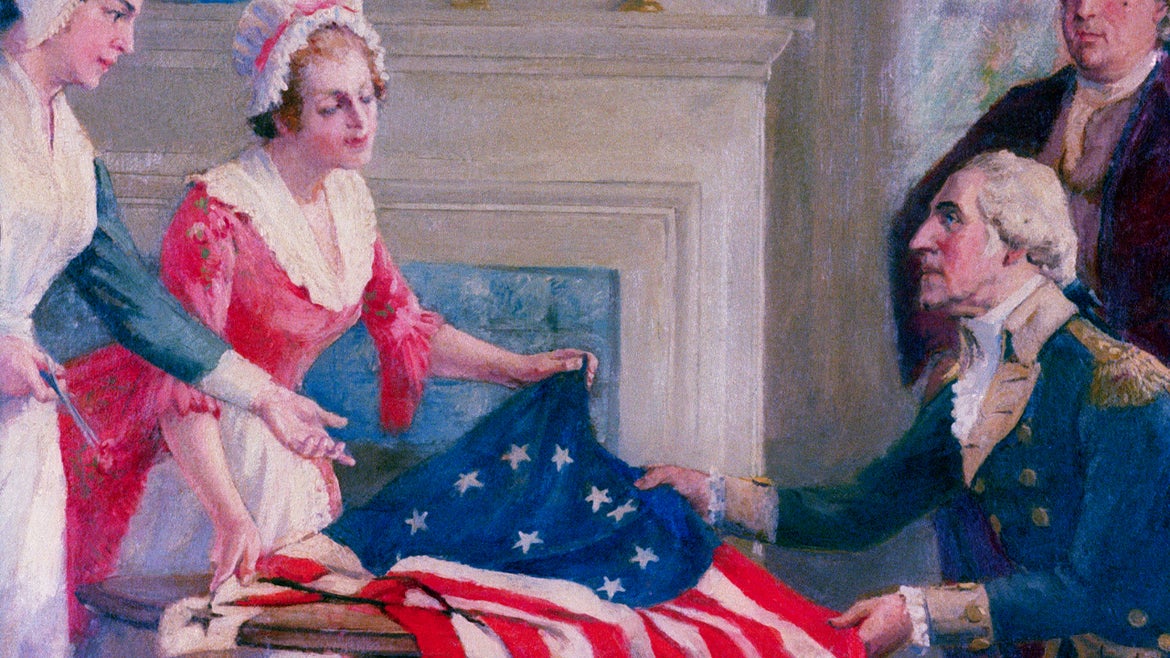

Betsy Ross has long been considered a patriotic symbol. She is thought to be the first person to sew the stars and stripes of the American flag in 1776.

Descendents of Bety Ross, considered one of America's most beloved patriots, gathered together in Philadelphia to commemorate their ancestor after her husband's old diary was unearthed.

The nearly 200-year-old journal belonged to Ross's third spouse, John Claypoole.

Born Elizabeth "Betsy" Griscom on Jan. 1, 1752 in Philadelphia, historians believe she is the first person to sew the "stars and stripes" U.S. flag in 1776. Betsy Ross was a Quaker and learned how to sew as a young woman while working for William Webster, an upholsterer. There, she sewed mattresses, rugs, umbrellas, tablecloths and window blinds, according to archives.

She met and fell in love with a fellow apprentice, John Ross, who would become her first husband. The two married and started an upholstery business together, but nearly two years later, John passed away.

It wasn't until years after her death when her grandson, William J. Candy, spread the legend of his grandmother in a speech on the history of the American flag in 1870. He claimed that Ross was approached by George Washington and other congressmen to create a flag for the new nation, according to National Geographic.

She supposedly convinced Washington to change the six-pointed stars to five-pointed because it would be easier to sew.

The history of Betsy Ross has been subject to much criticism over who was the first to sew the original design of the American flag.

While there is evidence that Ross was once paid 15 pounds to sew ship's standards by the Pennsylvania State Navy Board, there are also transactional receipts for other seamstresses during that time who would sew flags.

Before meeting Claypoole, Ross was married to her second husband, Joseph Ashburn, a sailor. She and Ashburn they had two daughters. Claypoole and Ashburn became friends while both prisoners of war in Britain's Old Mill Prison in Plymouth.

Ashburn died while incarcerated, but Claypoole was able to make it out. He then traveled to Philadelphia to deliver the unfortunate news of her husband's passing to Ross and after they met, the two married in 1783. They had five daughters together.

After the Treaty of Paris was signed and the Revolutionary War came to an end, Ross and her daughters would go on to sew upholstery and make flags and banners for the country.

All of this is explained in Claypoole's diary, which has now been donated to the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia. The Edges family, descendants of Ross and Claypoole, drove from San Francisco to the east coast to donate the forgotten artifact.

A family member found a box "randomly sitting in the garage," Aileen Edge, a lover of her family history, told the Moscow Pullman Daily News. "When we opened the box, we saw this small, wrapped-up book and it said it was the diary belonging to John Claypoole. And I thought, 'can this actually be something belonging to John Claypole!'"

They also found a Caypoole family Bible full of annotations that Claypoole's mother would write as early as the 1740s.

The Balderstons, also Ross-Calypoole descendants, donated a sea chest belonging to Claypoole in 2019. Both families gathered at the museum on Third and Chestnut Streets where they met for the first time.

For the time first, Claypoole's sea chest and diary also called a "memorandum book," were exhibited next to each other on Friday.

“That is just one of the most thrilling things that can happen in a museum — really reconstructing these stories using the objects that we can display,” Philip Mead, the museum's chief historian and curator, told the family, according to the Moscow Pullman Daily News,