A Moscow court outlawed foundations under Alexei Navalny Wednesday evening, designating them extremist organizations.

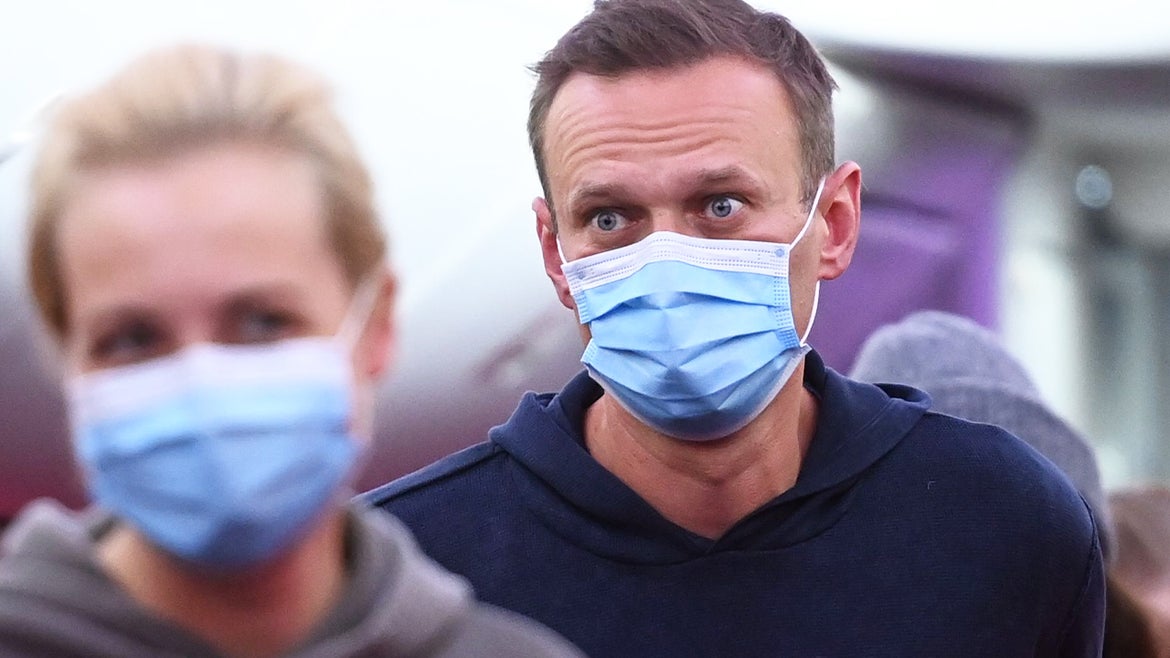

Russia’s Alexei Navalny, one of President Vladimir Putin’s biggest critics, continues to make headlines, despite being imprisoned for parole violation.

Since beginning his two-and-a-half-year sentence, he has been on hunger strike, accused prison authorities of state-sponsored torture and has seen his anti-corruption foundation outlawed and designated as an extremist organization.

But how did Navalny, a 44-year-old who started his career as a blogger, become Putin’s enemy number one?

Putin's Rise to Power

Putin had been involved in politics since before the fall of the Soviet Union. He held many high roles before being appointed Prime Minister under President Boris Yeltsin, who was praised for dismantling the Soviet Union and installing representative democracy to Russia.

Putin became acting president after Yeltsin’s sudden resignation at the end of 1999 and won the upcoming election, leading him to serve two terms as Russia’s president from 2000 to 2008. He had been largely a popular president then, improving Russia’s economy and living standards rapidly.

At the time, the Russian constitution allowed for only two consecutive terms of presidency. After Putin’s second term, he took the second-in-command position of Prime Minister under one-term president Dmitri Medvedev, who had previously served as Putin’s prime minister. Many saw Medvedev as Putin’s puppet leader.

The Kremlin also extended the terms of presidency in 2008, bringing them from four years to six years.

But Medvedev only served a four-year term and did not run for a second term, and toward the end of his presidency in 2011, Putin announced he would be president again. While many Russians knew of government corruption, attitudes toward Putin shifted at the outward disregard of the constitution, Vox reported.

Discontent against Putin came to a head in during the 2011 elections, when his party United Russia was accused of ballot-stuffing. The European Court of Human Rights ultimately declared the election was “unfair” and “compromised,” Insider reported.

Navalny’s Involvement

This was around the time when Navalny began making a name for himself as Putin’s greatest critic. He had been involved in Russian politics for about a decade at this point, and started sharing information about corruption at state-owned companies on his blog – a direct critique of Putin as president.

He quickly gained a huge audience, and eventually became the face of the protests in Moscow following the 2011 election.

Navalny’s Political Aspirations

Navalny has previously spoken out against running for the presidency, claiming he would never win, considering elections are not free or fair.

He eventually ran for mayor of Moscow on a nationalist platform despite many having hoped he would lead the liberalization of Russia.

He had been outspoken against other non-Russian ethnicities residing in Russia, calling for the deportation of illegal immigrants, supporting Russia in its 2008 war against Georgia and has been accused by close aids of using racial slurs, The Atlantic reported.

Navalny had instead called the criticisms “absolute nonsense,” and said his platform is actually “a basic, realistic agenda,” according to The Atlantic.

He eventually came in second for the mayoral race with 27% of the votes, beaten out by a pro-Putin candidate.

The Poisoning of Navalny

In August 2020, Navalny fell ill while on a flight from Tomsk, in Siberia, to Moscow, and the plane made an urgent landing in Omsk.

His spokesperson suspected that the tea he drank at the airport may have been spiked, and “the toxin was absorbed faster through the hot liquid,” she said on Twitter.

While some later reports said the water bottle in his hotel room was the culprit of the poisoning, one of the agents allegedly involved told Navalny, believing he was speaking to a Russian official, admitted that poison was applied to the inside of his underwear, so it would seep into his skin, CNN reported.

The hospital in Omsk would not have been sufficient for his treatment, and Navalny was eventually allowed by Russian officials to be airlifted to a secret location in Germany two days later.

There, investigators said he had been poisoned with Novichok, an advanced nerve agent and chemical weapon developed by the Soviet Union during the cold war, the BBC reported.

Navalny had been in a coma for 18 days, and eventually spent five months in Germany recovering, according to an Instagram post Navalny shared shortly after he regained consciousness, in which he said, “Putin has outsmarted me.”

The poisoning led to outrage by world leaders including German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who demanded a full explanation from the Kremlin, and the EU, which said that “those responsible must be brought to justice,” a statement read, according to the BBC.

Months later, ahead of Navalny’s return to Russia in January, Putin confirmed that Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) had in fact sent agents to tail Navalny after Bellingcat, an investigative news organization, first uncovered the finding, TIME reported.

Putin then added that if the objective was actually to kill Navalny, who was never referred to by name, “they would’ve probably finished it,” CNN reported.

Navalny's Return to Russia

Despite having been urged by Russian authorities not to return, Navalny flew to Moscow on Jan. 17, 2021, where he was immediately arrested by police at Sheremetyevo airport.

He was detained until his trial, where he was sentenced to a prison camp for two years and eight months for breaking the parole terms of his suspended sentence, and for allegedly having failed to appear for some probation appointments.

The previous sentence stemmed from a 2014 fraud trial that many called politically motivated, ABC News reported.

During the Soviet Union, many dissidents were given the choice to flee the country rather than risk arrest, and the pro-democracy movement usually encouraged its top figures to choose exile, according to The New Yorker.

But Navalny said he had never intended to not return to Russia. “The question ‘to return or not’ never stood before me. Mainly because I never left. I ended up in Germany, having arrived in an intensive care box, for one reason: they tried to kill me,” he said in an Instagram post shared the day after his arrival in Russia.

“His fight is in Russia and he did not do anything wrong,” Navalny’s colleague in anti-corruption work Vladimir Ashurkov told TIME. Ashurkov is currently living in exile in London.

This was also not his first time being jailed. Navalny had been jailed more than 10 times and up until this point, had spent hundreds of days in custody, RadioFreeEurope reported.

In at least one occasion, he was freed and had his sentence reevaluated after protesters raised objections about his imprisonment.

Imprisonment and Torture Allegations

Navalny was ordered to serve his sentence in Penal Colony Number 2 (IK-2), in the small town of Pokrov about two hours east of Moscow. In a Facebook post shared from his account, he called it a “real concentration camp” where cursing is prohibited, and compared the conditions to George Orwell’s dystopian novel "1984."

It is at this prison camp that Navalny alleged he was tortured. He said he was deprived of sleep, and was awoken by guards every hour throughout the night, but prison guards said it was necessary as he was deemed a flight risk, according to Reuters.

Others who have served time at the very same prison camp have also made allegations of torture. Activist and former prisoner Konstantin Kotov said that beatings on the soles of feet, long hours outdoors during the frigid winter and solitary confinement were commonplace, according to Deutsche Welle (DW), a German publication.

Kotov went on to tell CNN that prisoners in the camp are not allowed to talk to each other, and except for hours they are meant to be asleep, they are not allowed to sit down at all.

Additionally, Navalny said he started suffering from excruciating back pain, which progressed into numbness in his legs. He said he was only given ibuprofen and topical cream, which did not help, Reuters reported.

Sickness

In April, months into his sentence, Navalny fell “seriously ill” with symptoms for a respiratory illness, with coughing and a high fever, his lawyer said, according to The Guardian. He had also lost a lot of weight and suffered two hernias in addition to his severe back pain and numbness in the legs, his lawyers said, adding that there had been prisoners in his ward that came down with tuberculosis.

He ultimately tested negative for the coronavirus, his lawyer confirmed, according to ABC News.

Navalny said he demanded medical treatment from a civilian doctor, but was denied the request, according to Reuters. “His health is deemed stable and satisfactory, according to the results of the examination,” the penitentiary service said in response.

Hunger Strike

In response to what he said were mounting medical complications, Navalny declared on March 31 he would begin a hunger strike.

Less than a month later, and amid mass protests around Russia, his lawyers announced that he could be close to death, with heightened creatinine levels indicating kidney damage and elevated levels of potassium, which increases his chance of cardiac arrest, the AP reported.

“He was really unwell,” his lawyer Alexei Liptster said of Navalny’s condition days before he ended his strike, according to the AP. “Given the test results and the overall state of his health, it was decided to transfer him here [a hospital in a different prison]. In the evening, he became significantly worse.”

Navalny was urged to stop his hunger strike, and prison officials even threatened to force feed him in a “straitjacket,” he said on Instagram.

Navalny was moved to the prison ward of a hospital near Vladimir, another city 100 miles outside of Moscow that his doctor Anastasia Vasilyeva said is “not a hospital where a diagnosis can be determined and treatment (can be) prescribed for his ailments,” according to the AP.

He was eventually allowed to be treated by a civilian doctor, and said it was all thanks to his supporters, who relentlessly protested and even threatened to go on hunger strikes themselves, the AP reported.

What’s Next as Russia Outlaws Navalny's Foundation?

The tension between officials and Navalny’s Foundation for Fighting Corruption is higher than ever as Moscow City Court outlawed the group Wednesday, effective immediately, by labeling it an extremist organization.

This means Navalny’s allies and donors, who are seeking parliamentary seats, are barred from running from public office and could additionally be prosecuted and jailed, EuroNews reported.

This comes ahead of a crucial September election, the Associated Press reported.

The foundation also had many of its offices shut down by prosecutors in April.

Despite pushback, the foundation continued on with its work. Last month, it revealed details from an investigation into Putin’s secret home near Valdai, a town located on a lake between Moscow and St. Petersburg. The report from the group alleges that Putin's 75,000-square-foot home, a property complete with stables, a golf course and a cryotherapy chamber and flat pool in the spa area, was paid for using taxpayer money, The Guardian reported.