Madeline Lanciani, whose bakery, Duane Park Patisserie, has been in business in Downtown Manhattan for nearly 30 years, said she couldn't help but notice stark similarities between the COVID-19 pandemic and Sept. 11, 2001.

For Madeline Lanciani, the morning of Sept. 11, 2001 began like any other day. While she spent the early morning hours prepping her bakery kitchen in downtown Manhattan and taking note of inventory, American Airlines Flight 11 hit the North Tower of the World Trade Center. With her apron wrapped around her waist, she craned her head over her shoulder towards her two employees at Duane Park Patisserie. Their eyes opened wide in shock.

“I was right here at the bakery. I heard the first plane go right over my head and there was a boom,” she told Inside Edition Digital. “We all kind of looked at each other and said, ‘what was that?’”

She watched as crowds of people ran north, towards her store, which was just over a mile north of the attacks.

“All three of us walked out onto the sidewalk and went to the corner and saw this big giant hole. Flames burning out of the hole,” she said. Twenty years later, she said the same memories are stuck with her.

On that day, four commercial planes scheduled to fly from the East Coast to California were hijacked by nineteen terrorists who were tied to the Islamist extremist group al-Qaeda. Two of the jets were flown into the Twin Towers, which were part of the World Trade Center, located in the Financial District in lower Manhattan. The Twin Towers, at one point in time the tallest buildings in the world, fully collapsed before the world’s eyes, and by 9:30 a.m. that day, then-President George W. Bush made his first public remarks.

A third plane was flown into the Pentagon that day, where the U.S. Department of Defense is headquartered in Virginia. Passengers and crew members of a fourth plane headed toward Washington, D.C. were able to stop the hijacker and the plane ended up crashing into a field in rural Pennsylvania. The attacks killed 2, 977 people and resulted in the deaths of 441 first responders.

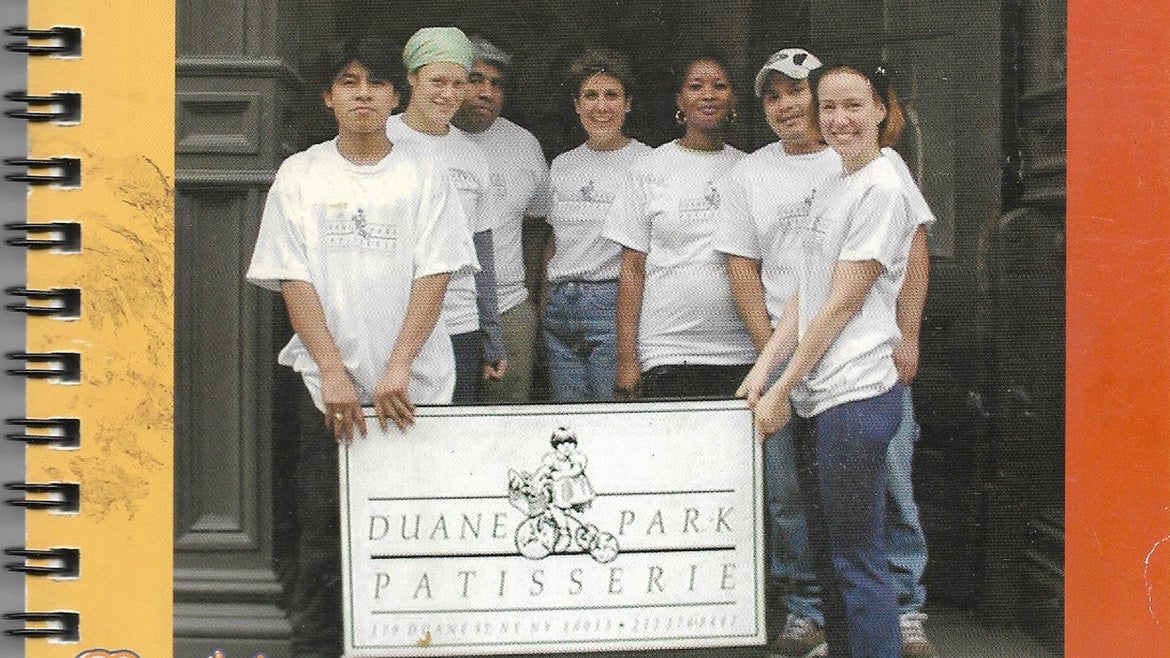

In 2001, Duane Park Patisserie had been open for nearly a decade. Today, 30 years after its opening, the bakery remains on the same corner of Greenwich and Duane Streets on the west side of Lower Manhattan.

Madeline recalled the moments eight strangers ran through the bakery’s open doors on that fateful day.

“We thought we were being bombed,” she said, remembering a pregnant woman who was among the group that ran inside. “The woman shouted ‘I need my purse!’ But I told her, ‘No, no purse. Get downstairs!’”

Madeline ushered the woman and a few others down into the basement where they sat in silence, awaiting a voice to appear from the static of her hand-held radio.

“People came in because my door was open. They came in to rest or regroup,” Madeline said. “Once people got in there and realized I had an analog phone, they lined up to call whomever they could call because the cell service wasn't working. It was a place to be and to collect themselves."

Though the shop just across the street didn't have electricity, Madeline said she had electricity until Tower Seven collapsed. “Duane street had a different power grid,” she reasoned. “I had power until 3 p.m. But I still had water, I had food, and basically, a place for people to stop.”

“We were eventually able to find out what was going on because of the radio. That's when we learned actually what happened.”

Her son was in middle school at the time on the Upper East Side and her daughter was at her high school in Brooklyn.

“The school called me to tell me everyone was OK. They had gathered all of the kids and told them that the Twin Towers had fallen down. I knew my son had to be safe because he was uptown. My best friend lived on Broad Street two blocks away, and her youngest son was a Sophomore at Stuyvesant High School. She came running up to the bakery and said 'are you OK? They're trying to ship me off to Staten Island.'”

A variety of boats and vessels off of the New York Harbor evacuated people who were stranded in Lower Manhattan. Staten Island ferries traveled back and forth all day, evacuating more than 50,000 people.

“When it was safe to leave the bakery, everyone just left. I never saw any of those people again. I have no idea what happened to any of them. It’s one of the things I would love to know,” Madeline said.

As soon as the electricity came back, Madeline decided to reopen her bakery.

”I needed routine, I needed some normalcy,” she said. “I’d pick up my staff in the Bronx, we started to clean everything including the debris, and we started to make small amounts of stuff. There were stations to feed the first responders so we would make things for them."

Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, when restaurants and bars were officially barred from operating as usual on March 17, the bakery took a major hit. Madeline said she lost 50% in revenue and had let go of 50% of her staff.

While restaurants across New York City eagerly awaited the impending re-opening of indoor dining, only a few Downtown establishments remained. Madeline, a self-proclaimed dinosaur of the Tribeca neighborhood, wishes others could have kept their doors open.

Reminiscing on the ever-changing neighborhood and landscape of food over the last three decades since she first opened, Madeline admitted that any sudden tragedy the neighborhood has encountered in the post-9/11 period—Hurricane Sandy, the 2008 recession, to name a few—was unparalleled to what took place on Sept. 11, 2001.

“The major change in Tribeca happened after 9/11,” she told Inside Edition Digital. In the '90s, Tribeca was glutted with artists, filmmakers and hippies, all of whom inhabited thrifty railroad-style lofts with a somewhat chastened appeal.

“It was a lot of artists, a lot of families, not too much business, less commercial, less intense than it is now. After Sept. 11, the demographics of the neighborhood certainly changed. Many longtime residents left and didn't come back. Because of that, real estate prices got very depressed. A new resident arrived post-9/11 and that trend continued to this day. But the same good schools and community spirit has remained the same.”

As she dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic, Madeline said she couldn't help but notice stark similarities to that fateful day.

“When your world gets turned upside down, you need normalcy and routine,” Madeline said. “I took a cue from my Sept. 11 playbook and knowing what I needed and knowing what I felt a lot of my neighbors needed. COVID has a lot more pernicious effect. It's still going on and we are still feeling the effects for a while.”

Asked what keeps her going every day, Madeline said, "Routine. Putting one foot in front of the other and just keep going. I know we are going to get out of this. I am going to hang in there and make sure my plan works."