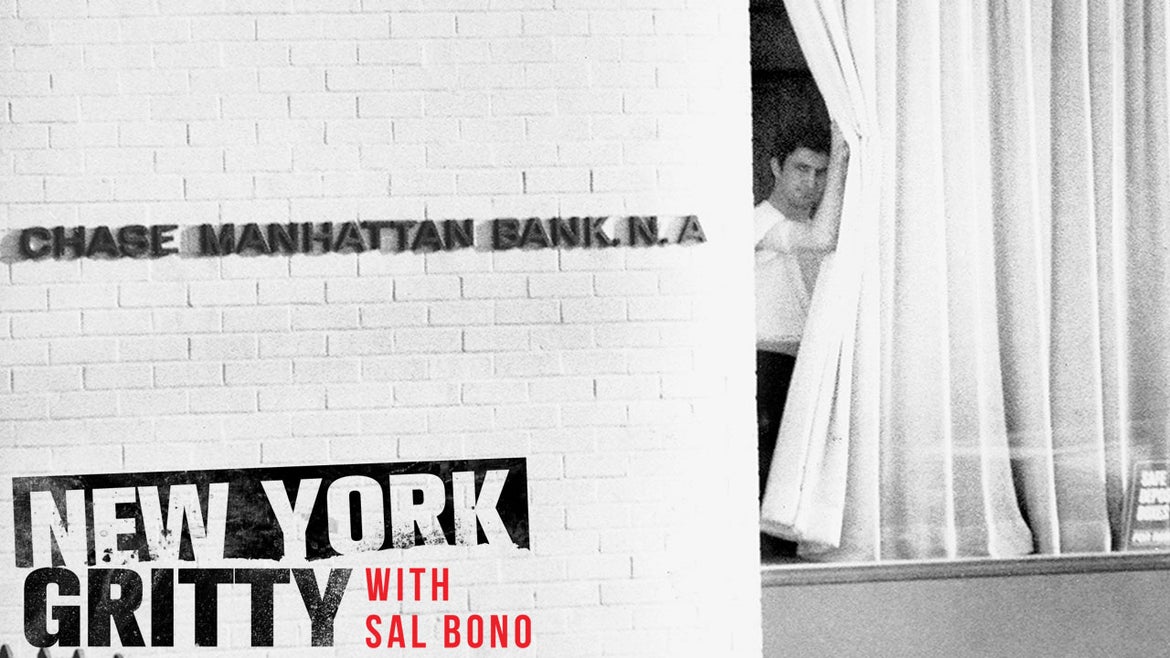

On Aug. 22, 1972, John Stanley Wojtowicz, Salvatore Naturile and Robert Westenberg attempted to rob a branch of the Chase Manhattan Bank in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Gravesend. What ensued would go on to inspire a film and become the stuff of legends.

It was a crime of passion that had every New Yorker on the edge of their seat in the summer of 1972.

Three armed men entered a bank in Brooklyn, ready to make off with a very large score.

They thought it would be a straight forward heist, but fate had other plans.

Unbeknownst to the robbers, the money held inside the vault had already been collected from the bank earlier in the day, leaving the branch with half of the funds expected and setting off a chain of events that would go on to inspire the making of a classic film.

How the Real "Dog Day Afternoon" Began

On Aug. 22, 1972, John Stanley Wojtowicz, Salvatore Naturile and Robert Westenberg attempted to rob a branch of the Chase Manhattan Bank in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Gravesend.

Within minutes of the robbers entering the bank, a teller triggered an alarm that alerted police to the crime unfolding. Cops dashed to the scene on Avenue P in and formed a perimeter around the bank. One of the three would-be robbers fled once police showed up.

The press had arrived as quick as law enforcement. The coverage of the crime was unlike anything anyone had seen before. All of the city was tuned into the robbery, either by radio or television, and it would hit every late edition of the local newspapers before the day was through.

Crowds from the neighborhood also formed, watching from outside the police perimeter. The already rapt audience was further engrossed in watching the case unfold after the leader of the charismatic bank robbers told the police and the press that they were holding up the bank to pay for a gender reassignment surgery for his lover.

This is how the crime that inspired the 1975 film "Dog Day Afternoon" started.

The Dog in His Cage

John Wojtowicz was born in 1945 and grew up in Brooklyn, New York, to a Polish father and an Italian-American mother.

The details of his upbringing have gone unreported, no anecdotes or stories from his childhood surviving the ensuing decades. But according to journalist and gay rights activist Randy Wicker, who befriended the family Wojtowicz, what's known for certain is he was star of a local baseball team as a teenager, and that he was brought up in a strict conservative family.

After graduating high school, Wojtowicz worked at various banks in the city. By his early twenties, he worked at his local Chase Bank in Flatbush, Brooklyn, where he met his girlfriend, Carmen Bifulco, who worked there as well.

The couple started dating in 1966, though her parents disapproved of their relationship, according to the BBC. The same year they began dating, he was drafted into the Army on March 29, according to military records obtained by The New York Times in 1972.

While in Vietnam, Wojtowicz had sexual experiences with men, according to Wicker.

“He went into the service. While in the service, he had gay sex, which he seemed to enjoy,” Wicker said.

He returned home from Vietnam in 1967 and immediately married Bifulco. The couple had two children, a boy and a girl and separated two years later after she reportedly found out about his affairs with men.

He was honorably discharged from the military on March 28, 1969, The Times reported. Since his release, he had been treated for four episodes of gonorrhea, the Times said.

The summer that Wojtowicz and Bifulco separated saw members of the LGBTQ+ community demand to be treated with respect. The Stonewall riots, protests that took place in response to a police raid of the Stonewall Inn in New York City on June 28, 1969, became a watershed moment for gay rights in America.

After he separated from his wife, Wojtowicz started calling himself LittleJohn Basso and began attending the Gay Activists Alliance's meetings at their West Village headquarters in a former firehouse.

GAA was founded in late 1969, months after Stonewall. The organization gave LGBTQ+ New Yorkers an opportunity to organize and fight for civil rights.

While Wojtowicz was a member, he caused a rift among those in the group, according to Wicker.

“His behavior was also somewhat outrageous,” Wicker said. “They used to have dances down at the GAA firehouse, and it was a normal kind of dance experience. You went out and, there might be some bumping and grinding or hot dancing on this dance floor, but nothing outrageous. But John Wojtowicz would literally grab somebody and fall on a couch by the coat room and start having sexual activity right there. And you just don't do that.”

Journalist Arthur Bell documented Wojtowicz antics in the Village Voice, writing, “John was pleasant, spunky, a little crazy, and up front about his high sex drive."

Wojtowicz was ostracized by much of the GAA due to his antics but he still attended functions and events, Wicker said.

In June 1971, at the annual Italian Feast of Saint Anthony in Little Italy, he met drag queen and sex worker Elizabeth Eden and fell in love.

Though still legally married to Bifulco, and 40 years before gay marriage was legalized in New York, Wojtowicz and Eden pledged their devotion to each other in a same-sex union in November 1971 at the GAA headquarters.

Their non-legally-binding marriage came on the heels of protests the GAA and Wojtowicz organized at the city clerk’s office for the right to a marriage license. And the marriage ceremonies that the GAA would hold would become pivotal in the push for marriage equality.

Wojtowicz’s wedding to Eden was one of the first of its kind that Wicker had ever witnessed. Wicker, a lifelong activist, was caught off guard.

“This was mind boggling,” Wicker said. “First, I never heard of a gay wedding before, and the idea that it was going to be a bride in drag, which was what we thought in those days. And the mother of the groom was going to be there.”

Ultimately, Wojtowicz and Eden's relationship would sour.

“He and Liz tried living together, but he apparently was very jealous and impossible to deal with. And he was also physically violent so she was afraid to get away from him. She tried to get away from him,” Wicker said. “No one could put up with John Wojtowicz. Nobody, except maybe his mother.”

Wicker says that Eden wanted to go through with a gender reassignment surgery but he says she was “terrified” of Wojtowicz because he “opposed” the process.

Less than a year into their marriage, Eden would attempt suicide multiple times and then in August 1972, while in the hospital being treated for self-inflicted harm, Eden was told she would be committed and given electroshock therapy, according to the 2013 documentary "The Dog." At the same time, Wojtowicz was concocting a plan that he believed would win his wife back and save his marriage.

A Real-Life “Dog Day Afternoon”

On Aug. 21, John Wojtowicz and two accomplices, Salvatore Naturile, 18, and Bobby Westenberg, 20, whom he knew through friends in the West Village, spent the night in a New Jersey hotel room haphazardly concocting a plan to rob a bank in New York.

The next day, they drove into Manhattan and began casing banks. They quickly ran into issues, which would continue to crop up as they continued on about their day. At one point in the day, their shotguns fell out of the car and they had to pick them up before attempting to rob one bank.

“[It was] a bungled job… They went down with a shotgun on Canal Street. It literally fell out of the back of the car, onto the street,” Wicker said. “With people walking by. And they picked it up and put it back in the car, and then they traveled around, looking for a bank to rob.”

At another bank, Westenberg noticed a friend of his mother’s and could not go through with the robbery. Outside another bank they hit a car as they practiced their getaway, Wojtowicz said in “The Dog.”

The motley crew, which evokes less of an “Ocean’s 11” vibe and and more of a “Three Stooges” air, even stopped at one point to see “The Godfather” at a Times Square movie theater to amp themselves up to rob a bank, Wojtowicz said in “The Dog."

Finally, around 3 p.m., the group walked into the Chase Manhattan Bank in Gravesend, Brooklyn. Armed with shotguns, the three men waited for the last customer to leave before launched into their half-concocted plan.

The plan was doomed from the get-go.

Once inside the bank, the men, who never concealed their faces, went to a teller with a “Godfather”-inspired note that read, “this is an offer you cannot refuse.”

As quickly as a teller was able to trigger the bank's alarm, their plan was foiled. As police sirens converged on the bank, Westenberg took off, leaving Wojtowicz and Naturile on their own.

Within minutes, police outside the bank demanded the criminals come out. When Wojtowicz and Naturile refused, the robbery turned into a hostage situation. Eight bank staffers sat captive as police outside established a headquarters inside a neighboring beauty parlor and snipers set up on nearby roofs.

To add issues to the criminals’ plans, the safe was half empty, according to the BBC.

Negotiations with Wojtowicz began as more than 2,000 people from the neighborhood gathered to see what was happening, BBC reported. Wojtowicz also spoke to the press from inside the bank, giving interviews to any journalist who called the bank directly.

“It's the first time that the media had covered something like that, continuously, and of course, it was an unfolding drama,” Wicker said.

Like every New Yorker, Village Voice journalist Arthur Bell was fascinated by what was unfolding in Brooklyn. After making calls to gather more information to cover the story, he learned that Wojtowicz, who he knew as LittleJohn Basso from GAA, was behind the caper.

“I phoned John [Wojtowicz] at the bank again to tell him I was on my way,” Bell wrote in the Village Voice in 1972.

Bell, along with police negotiators, pressed Wojotwicz to surrender while trying to flesh out his motive.

Bell later wrote that Wojotwicz "gave me the phone number of the female wife whom he had separated from, to call in case anything happened."

Convinced he wouldn't be walking out of the bank alive, Wojotwicz also told Bell "That money, I wanted it for a sex change operation for [Eden.] Now I can’t even see him to kiss [her],’” Bell wrote.

The World Learns What Led Wojtowicz to Try to Rob a Bank

Bell raced over to the crime scene. By the time he arrived, Wojtowicz had told police he wanted money for his wife's gender reassignment surgery. The news was made public.

Some in crowd turned ugly when learning of Wojtowicz's motive. When a police officer called Wojtowicz a gay slur, Wojtowicz ran outside and threatened the cop, causing even more of a raucous.

But Wojtowicz also had a plan to endear the crowd to him.

Wojtowicz demanded that his hostages be fed, and when authorities arrived with pizza, Wojtowicz began throwing money to the onlookers. Once word got out that money was being thrown out by the crooks, more people showed up.

“The crowd loved it…they were all rooting for [Wojtowicz]. He came out and threw away, I don't know how many dollars, a few thousand. He threw away handfuls of money, up in the air, and this mob starts surging to grab the bills that are being blown down,” Wicker said.

Authorities tried everything to coax Wojtowicz to give up. They felt he would be the best person to deal with to end the siege rather than Naturile, who hostages believed was trigger happy, the BBC reported. The stand-off would go on for 14 hours.

The FBI also tried coaxing Wojtowicz into surrendering. At law enforcement's behest, Wojtowicz's former lover arrived to try speaking with him. The pair kissed in the doorway of the bank, receiving jeers from the crowd outside. Wojtowicz's mother, Terry, also arrived on the scene to speak to her son.

“At one point, his mother was out there, hysterical, ‘My son, my son!’ And they told her, ‘Mrs. Wojtowicz, we think we can save John. Sal is the real problem.' But Sal also is the one that had the gun,” Wicker said.

But all Wojtowicz wanted was Eden.

Eden was brought from Kings County Hospital to the scene, but she didn’t want to see Wojtowicz, instead choosing to remain with police at their makeshift headquarters. She told Bell that she refused to see her husband because despite his charming persona, he was a monster.

“[Wojtowicz] was also good-natured, and that was the problem. John and I couldn’t live together because of mental problems on both sides. It would never have worked out. John was sadistic in his sex habits. He could control himself, but sometimes he went overboard with such things and he terrified me,’” Eden told Bell, he wrote in the Village Voice.

With no end-game in sight, authorities began giving in to some of Wojtowicz’s demands. They promised him and Naturile plane tickets to Europe. They also said Eden would have a ticket so she could get her gender-reassignment surgery.

FBI agents driving a van arrived at the bank and transported Wojtowicz, Naturile, Eden and the hostages to JFK Airport in Queens. As soon as they arrived at the airport, Naturile was shot and killed by the FBI and Wojtowicz was arrested.

“Sal was somebody who had a criminal record, had been in jail. He was the muscle,” Wicker said. “He was determined. He would rather die than go back to prison. He was not going to go back to prison, period.

"The minute the agent shot Sal, John jumped out of the back seat of the car with his hands in the air and gave up," Wicker said.

The hostages were freed and walked away physically unharmed.

Not Every Dog Has His Day

Three days after the heist, Westenberg surrendered to police. He would later plead guilty to conspiracy charges in connection with the case and was sentenced to two years in prison, according to The New York Times. Attempts made by Inside Edition Digital to reach Westenberg for comment were unsuccessful.

After his arrest, reporters learned that Wojtowicz had previously sought psychiatric treatment. The New York Times reported two days after the robbery that “the V.A. said he had declined psychiatric help from its hospital in Brooklyn. At St. Vincent's Hospital in Manhattan, it was reported that he appeared one day at the clinic for an interview and never returned.”

“He's not a mean kid. He's not the type who would hurt anybody. He's disturbed," Terry Wojtowicz told The New York Times.

Wojtowicz's actions brought shame to the family, his mother said. His father learned of the bungled bank robbery after getting off from work. It was only then that he saw his son’s face plastered on every newspaper at the newsstands, she said in “The Dog." The patriarch, she said, didn't go to work for two weeks because of the shame of what his son had done.

Behind bars while awaiting his sentencing, Wojtowicz lapped up in his celebrity status.

The media circus around the case had Hollywood calling and in 1973, Wojtowicz was paid for his rights to the story. “Dog Day Afternoon,” starred Al Pacino as a character inspired by Wojtowicz and was directed by Sidney Lumet.

Wojtowicz gave the money he received for his rights to the story to Eden for her gender reassignment surgery.

The GAA heavily debated whether they should support Wojtowicz. Some saw him as a liability to the Gay Rights movement, while others felt that his was a cause they should back.

“This was a guy who was a scandal within the gay community! The way he behaved and everything, no one wanted anything to do with him,” Wicker said.

Weeks after his arrest, Arthur Bell made the sensational claim that the heist was actually a mob bust gone wrong in a Village Voice article. The story caught everyone’s attention and caused the GAA to distance themselves further from Wojtowicz’s case, Wicker said.

Wicker said that Bell’s story was the “final nail in the coffin” for GAA to support the criminal.

“Arthur Bell said that it wasn't really robbing, it was really a mafia plot, so to speak, in conspiracy theory language. Because that's really what it essentially was,” Wicker said. “This gave the gay community the opportunity to totally disassociated themselves from it.”

The mafia ran many New York gay bars, but they were no allies to the LGBTQ+ community. "They had used us and exploited us for years,” Wicker said.

The suspicion that Wojtowicz was working for the mob was inspired by his partial Italian lineage and had no base in reality, Wicker said. The theory has never been proven, and no organized crime syndicate has ever claimed responsibility for the failed bank robbery.

"He was crazy. I mean nobody, no criminal organization would've ever gotten involved [with him]," Wicker said.

While in jail awaiting trial, Wojtowicz attempted to take his own life, but survived.

Wojtowicz pleaded guilty to the charges he faced and on April 23, 1973, he was sentenced to 20 years in Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary.

While in prison, he met George Heath, a “jailhouse lawyer,” who helped Wojtowicz during his appeal process.

A “jailhouse lawyer” is “certain prisoners in prison who maybe are more intelligent, or would spend some time educating themselves on the law, and would volunteer and, or maybe get a pack of cigarettes from other prisoners to write these appeals for them," Gary Woodfield, a former Assistant New York D.A. explained to Inside Edition Digital. "And some of them got very good at it. And there are some stories where some of these jailhouse lawyers, when they got out of prison, became paralegals in law firms.”

While Wojtowicz was in prison, “Dog Day Afternoon” was released in 1975 to critical and commercial acclaim.

Wojtowicz began insisting he only be referred to as “The Dog.” His newfound fame in prison also put a target on his back, according to Wicker, who said that if it wasn’t for Heath’s protection, Wojtowicz would have likely been killed while in prison.

“John would've been killed in prison, because in prison, John started bragging about ‘they're making a movie about me,’ and when the movie came out, he demanded that they show the whole prison the movie,” Wicker said. “There was actually a petty jealousy on that level.”

The film was nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, and Pacino landed a Best Actor nod. It won Best Screenplay and has been hailed as one of the best films of the 1970s. The American Film Institute hails it as one of the 100 best films ever made.

Gary Woodfield prosecuted Wojtowicz’s 1977 appeal for the State of New York.

“This guy struck me as being an intelligent guy who screwed up, in a layman sense. He was a smart guy and above average intelligence, but he certainly had his issues,” he told Inside Edition Digital.

Woodfield ordered Wojtowicz undergo a psychiatric evaluation ahead of the appeal.

“I think I communicated with the doctor that performed that analysis, but I never did see him at any point in time,” Woodfield said. “And that's not unusual… So there were some nut balls, and John was one of them.”

While dealing with appeals from others in similar positions to Wojtowicz, Woodfield recalled this case being special because of its Hollywood connection.

“This one was kind of special, because Al Pacino was in the movie,” he said. “I appreciated the assignment, and it was certainly out of the ordinary…I didn't think there was a great argument here, although he had some, but it certainly took on a different character because of the movie, no doubt about it. I don't know what happened in that bank, and whether the movie was anything close to reality.”

Wojtowicz was ultimately resentenced and served five years in prison before being paroled.

Wojtowicz and Heath, who pledged themselves to each other in a civil union in prison, were both released separately in 1978. They moved in together with Wojtowicz’s parents in their Brooklyn home.

Barking for Attention

Eden underwent a gender reassignment surgery. She said in a 1978 television interview after the release of her former husband that she wanted nothing to do with him. In that same interview, Wojtowicz told her he was proud of what he did because he believed it saved her life.

Eden eventually left New York City and settled in Rochester, a city about five hours away on Lake Ontario in New York State. There she worked as a sex worker. She died from AIDS in 1987.

Wojtowicz struggled to find steady work, even going so far as applying for the role of head of security at the Chase Bank he held up. They turned him down.

Wojtowicz would often make appearances outside that bank, charging people for autographs and pictures while wearing a shirt that said, “I Robbed This Bank,” the New York Post reported.

Wojtowicz and Heath eventually separated. He continued to date, entering into relationships that often evolved into living together at Wojtowicz's parents' home in Brooklyn. There, his mother would help care for them as long as they stayed, Wicker said.

“The mother would be there and if John... [brought someone] home, his mother would hop out of bed to run and fix dinner,” Wicker explained.

Wojtowicz's relationship with his mother would go down in history as his most steady and loving. "She was totally devoted" to her son, Wicker said, especially after the passing of her husband, who died not long after Wojtowicz's release from prison.

“She was just absolutely giving and tolerant and loving,” Wicker said.

Wojtowicz had a hard time staying out of trouble and was arrested again for violating his parole in 1987, according to The Telegraph. In 2001, The New York Times reported that Wojtowicz was living on welfare. A few years later, he was diagnosed with cancer. He died in January 2006. He was 60.

His mother kept his ashes in their Brooklyn home before she died months later in October 2006. She was 85.

Bifulco, who officially divorced Wojtowicz in the 1980s, never remarried and died in 2013. The whereabouts of Wojtowicz's children are unknown.

Woodfield is still practicing law and remembers the Wojtowicz case as "special."

"I appreciated the assignment, and it was certainly out of the ordinary," he said.

“It was a fun job at a fun time,” Woodfield continued. “This case because of Al Pacino, because of the movie, I mean, just the very concept of what this guy was up to was just pretty unique.”

Related Stories